3rd Dec, 2021 13:00

Fine Japanese Art

87

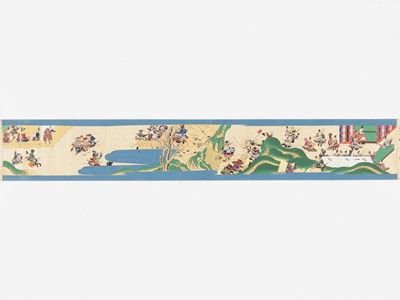

AN EXTREMELY RARE AND HIGHLY IMPORTANT SET OF THREE SCROLL PAINTINGS, WITH A TOTAL LENGTH OVER 55 METERS, DEPICTING THE SAMURAI WARS OF 1083

GOSANNEN KASSEN EKOTOBA (SCROLL OF THE LATER THREE YEARS’ WAR)

Sold for €37,920

including Buyer's Premium

Painted by Imamura Zuigaku Yoshitsugu (died in 1793)

Japan, dated 1780, Edo period (1615-1868)

Three handscrolls, painted with ink, watercolors, and gold on paper, each with a silk brocade frame.

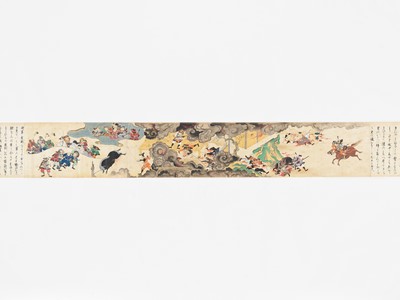

The handscrolls are an old reproduction of the famous emaki painted by Hidanokami Korehisa in 1347, which is now an Important Cultural Property in the collection of the Tokyo National Museum and was itself a copy after the original emaki painted in 1171, which is now lost. They tell the story of a largescale battle over power between two samurai groups, Minamoto no Yoshiie and Kiyohara no Iehira during the Heian Period. Yoshiie, the governor of Mutsu, defeated the Kiyohara clan of Dewa by taking advantage of their inner conflict. Following the Zen Kunen no Eki (battles that took place in Oshu in the late Heian period), the Gosannen Kassen began in 1083 and ended in 1087 when Yoshiie seized Kanazawa-saku, a stronghold of Kiyohara no Iehira and others, subjugating the Oshu region.

Scroll 1 (Vol. 1): SIZE 46 x 1,866 cm

Scroll 2 (Vol. 2): SIZE 46 x 1,705 cm

Scroll 3 (Vol.3): SIZE 46 x 1,964 cm

Condition: Each scroll in a superb state of preservation with fresh colors, the scrolls were evidently stored well and only very rarely opened. Some minor non-distracting surface wear, little soiling and creasing, few minuscule losses and tears.

Provenance: From an old French private collection.

Emaki, also called emakimono (or less commonly ekotoba), is an illustrated horizontal narration system of painted handscrolls that dates back to the Nara period in 8th century Japan, initially copying its much older Chinese counterparts. They combine calligraphy and illustrations and are painted on long rolls of paper or silk sometimes measuring several meters. The reader unwinds each scroll little by little from right to left, revealing the story as seen fit. Emakimono are therefore a narrative genre similar to the book, developing romantic or epic stories, or illustrating religious texts and legends. The format of the emakimono, long scrolls of limited height, requires the solving of all kinds of composition problems: it is first necessary to make the transitions between the different scenes that accompany the story, to choose a point of view that reflects the narration, and to create a rhythm that best expresses the feelings and emotions of the moment. In general, there are thus two main categories of emakimono: those which alternate the calligraphy and the image, each new painting illustrating the preceding text, and those which present continuous paintings, not interrupted by the text, where various technical measures allow the fluid transitions between the scenes. Today, emakimono offer a unique historical glimpse into the life and customs of Japanese people, of all social classes and all ages, during the early part of medieval times.

Only few of the original scrolls have survived intact, with around 20 being protected as National Treasures of Japan, and many have been either partly or entirely lost. However, due to the importance of certain emaki, faithful reproductions, known as mohon, were made through the centuries. Some of these reproductions, particularly older ones such as the present lot, as well as copies of lost scrolls and those painted by noted artists, are considered as valuable as the originals.

The stirring events of the Later Three Year War were first recorded in pictorial form during the late Heian period. The earliest known depiction was a set of four scrolls executed in 1171 at the order of Go-Shirakawa (1127-1193) by the painter Akizane; this was one year after Fujiwara Hidehira had been given control over Mutsu and Dewa and the Fujiwara family thus celebrated some of the events that had led to their gaining power equal to that of the Taira clan in the capital. While this set has not survived, the Tokyo National Museum has a set of three scrolls (formerly in the Ikeda collection) that date to the 14th century and are the earliest extant renditions of the subject. This set bears a preface written by Gen-e in 1347 and is thus known as the Gen-e version.

The Gen-e version constitutes only half of an original set of six scrolls, but at least the content of the missing sections can be deduced from a literary record, the Oshu Gosannen Ki (Record of the Later Three Years War). In addition, there is a set of four pictorial scrolls, now in the Okayama Prefectural Museum, that was done in 1719 when the literary record was copied; this set preserves some of the opening scenes but is still missing some sections. Finally, there is an account left by Yasutomi who in 1444, at Ninna-ji, looked at one set, likely the earliest, no longer extant version from 1171, and described the scenes.

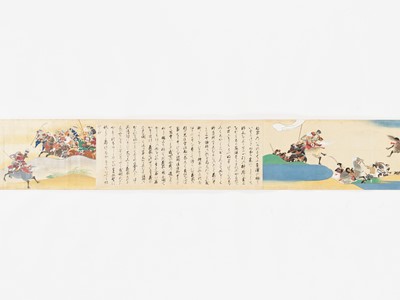

The present set of scrolls are faithfully copied from the Gen-e version in the Tokyo National Museum, the scenes and calligraphy being an exact match other than the dating and inscription on the third scroll: 安永九年庚子八月、今村 随學甫紹寫 “An’ei kyunen kanoe-ne hachigatsu, Imamura Zuigaku Yoshitsugu utsusu” [Copied and painted by Imamura Zuigaku Yoshitsugu, in the 8th month of the year of Kanoe-ne, An’ei 9th year (1780)].

Imamura Zuigaku Yoshitsugu (died in 1793). His year of birth is unknown. The artist first studied under Kano Zuisen Yoshinobu 狩野随川甫信 (1692-1745), thus inheriting the two characters 随 (zui) and 甫 (yoshi ) from his master. Then Imamura Zuigaku studied further under Kano Josen Yukinobu 狩野常川幸信 (1717-1770). These Kano painters were the second and third generation heads of the Hamamachi line of the Kano School respectively. In Meiwa 4 (1767), Imamura Zuigaku was appointed an official painter to the Owari Domain, one of the Three Houses of the Tokugawa (The Tokugawa Gosanke 徳川御三家).

Imamura Zuigaku painted an emaki scroll of the Heiji Monogatari (平治物語絵巻 ), copied from an earlier edition. It is known that this Heiji Monogatari scroll was painted in 1781 (Tenmei 1) for Tokugawa Munechika (1733-1800, ruled 1761-1799), the 9th generation Daimyo of the Owari Domain. Therefore, most likely the present set of highly important emaki scroll paintings were commissioned by imperial decree for Tokugawa Munechika.

Additionally, there is a dating on the colophon corresponding to the 10th month of 1701 (Genroku 14). The reason for this is that Lady Ryoshoin (Tokugawa Ieyasu’s daughter,1565-1615) was in possession of a set of Gosannen War Scroll. However over the years the scrolls (Lady Ryoshoin’s scroll treasure) were damaged. In Genroku 14 (1701), her scrolls were restored in Kyoto. The emperor inspected the scrolls and praised them.

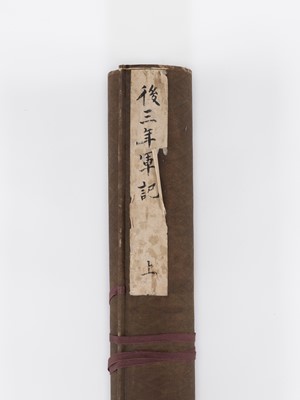

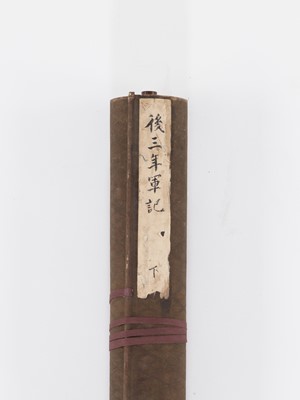

The exterior of each scroll applied with an old paper label showing the title (The Chronicle of the Later Three-Year War) and which volume it is.

Literature comparison:

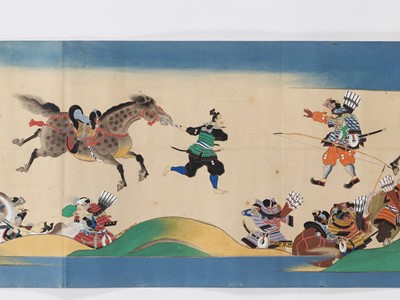

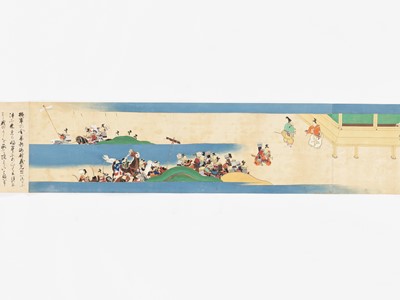

The emaki by Hidanokami Korehisa dated 1347 (the ‘Gen-e version’), the oldest one among existing picture scrolls on the Gosannen Kassen, is an Important Cultural Property in the collection of the Tokyo National Museum, accession number A-11187. Compare three scrolls with a reproduction of the 1347 scrolls dated 1913, reproduced by the Tokyo Archaeological Association, in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, accession numbers 17.235.9-.11. Compare also closely related but later set of three handscrolls by Sumiyoshi Hirotsura (1793-1863), dated 1853, illustrated in Kaikodo Journal (2000) In the Eye of the Beholder, p. 124-125, no. 31.

Auction comparison:

Compare a scroll (42.3 x 1,928.2 cm) of the first volume, dated to the 18th century, at Christie’s, Japanese Works of Art, 1 November 1996, New York, lot 357 (sold for 14,950 USD, for a single scroll).

Compare to a related singular emaki scroll, measuring 32.5 x 1,624.3 cm, from the Illustrated Scrolls of the Chronicle of Great Peace (vol. II from the set of 12 volumes), dated to mid-17th century, sold at Christie’s, 20 March 1996, New York, lot 407 (sold for USD 288,500).

VOLUME 1

SECTION 1

After hearing that Iehira drove away Governor Yoshiie, Takehira arrives to congratulate Iehira and advise him to move to the more secure and defensible Kanazawa stockade. Takehira and Iehira talk together in the garden while to the left Takehira’s troops set out for the stockade.

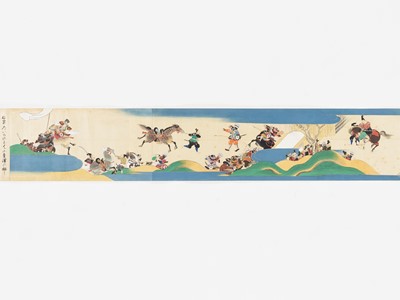

SECTION 2

Yoshimitsu, the brother of Shogun Yoshiie, resigns his position in office on account that the Retired Emperor did not grant his appeal to join his brother in the life or death battle against Takehira. Now, with Yoshimitsu on the battlefield, the frontal forces of Yoshiie begin their attack on the Fort. Members of the fort fight back with arrows and one of them injures Kagemasa of Sagami, who fought recklessly against the enemy. The arrow has gone through Kagemasa’s helmet and pierces him in his right eye. Kagemasa breaks off a part of that arrow and throws it back at the enemy, then takes off his helmet to announce his injury. Yoshiie’s soldiers are still unable to break through the fort.

SECTION 3

Governor Yoshiie becomes angry after learning that Takehira has joined allegiance with Iehira and sets off for Kanazawa. The ladies of his household sob at the windows of the house as they watch him mount his horse, which is being held by Mitsutada, an eighty-year-old veteran of the Former Nine Years War but now obliged by age to remain at home, regretful of his inability to join his master.

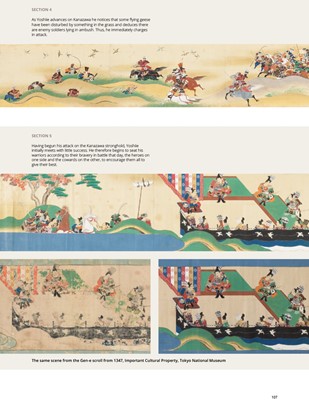

SECTION 4

As Yoshiie advances on Kanazawa he notices that some flying geese have been disturbed by something in the grass and deduces there are enemy soldiers lying in ambush. Thus, he immediately charges in attack.

SECTION 5

Having begun his attack on the Kanazawa stronghold, Yoshiie initially meets with little success. He therefore begins to seat his warriors according to their bravery in battle that day, the heroes on one side and the cowards on the other, to encourage them all to give their best.

VOLUME 2

SECTION 1

Yoshihiko Hidetake has suggested that the stronghold be surrounded with a blockade to prevent any supplies from being brought into the keep. To pass the time, Takehira proposed that each side choose a champion and have them fight together. In the center of this scene, Onitake on the right and Kametsugu on the left prepare to do battle with naginata (long-handled weapons).

SECTION 2

With Onitake on the verge of winning the bout, Yoshiie’s warriors give a great shout of triumph, at which Takehira’s soldiers pour out of the stronghold to rescue their champion Kametsugu from certain death. In the ensuing carnage one of the fatalities is Korehiro, who had been classed earlier as a coward and was determined to win respect on this day.

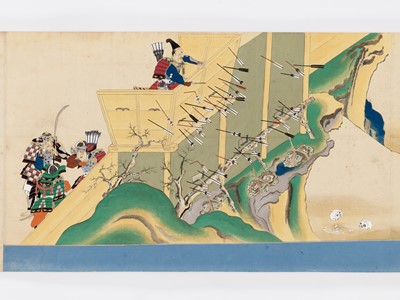

SECTION 3

Standing at the top of the fortifications, Sentada, adviser to Iehira, shouts loudly down to Yoshiie: “Your father Yoriyoshi was given much trouble by Sadatada and Munetada during the previous war but he destroyed them with the assistance of our master, who served him loyally. Now you attack his descendants. May you be punished by Heaven for your disloyalty and unfaithfulness.”

SECTION 4

As the stronghold runs short of food, Takehira proposed to Yoshimitsu that they surrender but this offer is refused by Yoshiie. Takehira then invites Yoshimitsu into the castle but Yoshimitsu refused and a warrior named Suekata goes in his place. Takehira asks him to intercede with Yoshiie, and shows him an exceptionally large arrow and asks whose it is. Suekata replies that it is his and returns to his own camp.

SECTION 5

As autumn turns to winter, Yoshiie’s warriors begin to worry that they will freeze to death and write letters to send together with their extra clothes and horses to their families with instructions to sell these belongings and return to Kyoto if they should die. As food becomes scarce, women and children gradually come out but are killed on Hidetake’s advice to keep the remainder within and use up the food remains even faster.

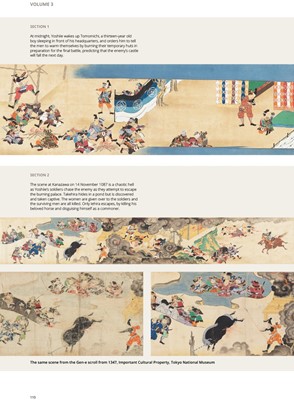

VOLUME 3

SECTION 1

At midnight, Yoshiie wakes up Tomomichi, a thirteen-year old boy sleeping in front of his headquarters, and orders him to tell the men to warm themselves by burning their temporary huts in preparation for the final battle, predicting that the enemy’s castle will fall the next day.

SECTION 2

The scene at Kanazawa on 14 November 1087 is a chaotic hell as Yoshiie’s soldiers chase the enemy as they attempt to escape the burning palace. Takehira hides in a pond but is discovered and taken captive. The women are given over to the soldiers and the surviving men are all killed. Only Iehira escapes, by killing his beloved horse and disguising himself as a commoner.

SECTION 3

With Takehira kneeling before him, Yoshiie recounts the crimes he has committed and orders Oya Mitsufusa to chop off his head. Takehira asks Yoshimitsu for mercy but to no avail. Next, in the scene to the far left, Sentada is brought before Yoshiie, who hates him bitterly for what he shouted from the safety of the fortress. Yoshiie thus orders his tongue to be pulled out and that he be tied to a tree with the head of Takehira beneath him, so that he stands on his dead master’s face. The fortress meanwhile burns to the ground.

SECTION 4

A warrior named Tsugitada has seen the refugees run from the castle and discovers Iehira dressed as a laborer. Tsugitada kills him and presents his head to Yoshiie, who is so delighted that Tsugitada is granted a red robe and horse with saddle.

SECTION 5

Yoshiie makes his report on the war to the court in Kyoto, trying to convince them that he fought on behalf of imperial interests. However, the court disallows the claim, judging that the war had been fought for private purposes. Yoshiie thus understands that he will not receive any reward or even expenses from the court.

Painted by Imamura Zuigaku Yoshitsugu (died in 1793)

Japan, dated 1780, Edo period (1615-1868)

Three handscrolls, painted with ink, watercolors, and gold on paper, each with a silk brocade frame.

The handscrolls are an old reproduction of the famous emaki painted by Hidanokami Korehisa in 1347, which is now an Important Cultural Property in the collection of the Tokyo National Museum and was itself a copy after the original emaki painted in 1171, which is now lost. They tell the story of a largescale battle over power between two samurai groups, Minamoto no Yoshiie and Kiyohara no Iehira during the Heian Period. Yoshiie, the governor of Mutsu, defeated the Kiyohara clan of Dewa by taking advantage of their inner conflict. Following the Zen Kunen no Eki (battles that took place in Oshu in the late Heian period), the Gosannen Kassen began in 1083 and ended in 1087 when Yoshiie seized Kanazawa-saku, a stronghold of Kiyohara no Iehira and others, subjugating the Oshu region.

Scroll 1 (Vol. 1): SIZE 46 x 1,866 cm

Scroll 2 (Vol. 2): SIZE 46 x 1,705 cm

Scroll 3 (Vol.3): SIZE 46 x 1,964 cm

Condition: Each scroll in a superb state of preservation with fresh colors, the scrolls were evidently stored well and only very rarely opened. Some minor non-distracting surface wear, little soiling and creasing, few minuscule losses and tears.

Provenance: From an old French private collection.

Emaki, also called emakimono (or less commonly ekotoba), is an illustrated horizontal narration system of painted handscrolls that dates back to the Nara period in 8th century Japan, initially copying its much older Chinese counterparts. They combine calligraphy and illustrations and are painted on long rolls of paper or silk sometimes measuring several meters. The reader unwinds each scroll little by little from right to left, revealing the story as seen fit. Emakimono are therefore a narrative genre similar to the book, developing romantic or epic stories, or illustrating religious texts and legends. The format of the emakimono, long scrolls of limited height, requires the solving of all kinds of composition problems: it is first necessary to make the transitions between the different scenes that accompany the story, to choose a point of view that reflects the narration, and to create a rhythm that best expresses the feelings and emotions of the moment. In general, there are thus two main categories of emakimono: those which alternate the calligraphy and the image, each new painting illustrating the preceding text, and those which present continuous paintings, not interrupted by the text, where various technical measures allow the fluid transitions between the scenes. Today, emakimono offer a unique historical glimpse into the life and customs of Japanese people, of all social classes and all ages, during the early part of medieval times.

Only few of the original scrolls have survived intact, with around 20 being protected as National Treasures of Japan, and many have been either partly or entirely lost. However, due to the importance of certain emaki, faithful reproductions, known as mohon, were made through the centuries. Some of these reproductions, particularly older ones such as the present lot, as well as copies of lost scrolls and those painted by noted artists, are considered as valuable as the originals.

The stirring events of the Later Three Year War were first recorded in pictorial form during the late Heian period. The earliest known depiction was a set of four scrolls executed in 1171 at the order of Go-Shirakawa (1127-1193) by the painter Akizane; this was one year after Fujiwara Hidehira had been given control over Mutsu and Dewa and the Fujiwara family thus celebrated some of the events that had led to their gaining power equal to that of the Taira clan in the capital. While this set has not survived, the Tokyo National Museum has a set of three scrolls (formerly in the Ikeda collection) that date to the 14th century and are the earliest extant renditions of the subject. This set bears a preface written by Gen-e in 1347 and is thus known as the Gen-e version.

The Gen-e version constitutes only half of an original set of six scrolls, but at least the content of the missing sections can be deduced from a literary record, the Oshu Gosannen Ki (Record of the Later Three Years War). In addition, there is a set of four pictorial scrolls, now in the Okayama Prefectural Museum, that was done in 1719 when the literary record was copied; this set preserves some of the opening scenes but is still missing some sections. Finally, there is an account left by Yasutomi who in 1444, at Ninna-ji, looked at one set, likely the earliest, no longer extant version from 1171, and described the scenes.

The present set of scrolls are faithfully copied from the Gen-e version in the Tokyo National Museum, the scenes and calligraphy being an exact match other than the dating and inscription on the third scroll: 安永九年庚子八月、今村 随學甫紹寫 “An’ei kyunen kanoe-ne hachigatsu, Imamura Zuigaku Yoshitsugu utsusu” [Copied and painted by Imamura Zuigaku Yoshitsugu, in the 8th month of the year of Kanoe-ne, An’ei 9th year (1780)].

Imamura Zuigaku Yoshitsugu (died in 1793). His year of birth is unknown. The artist first studied under Kano Zuisen Yoshinobu 狩野随川甫信 (1692-1745), thus inheriting the two characters 随 (zui) and 甫 (yoshi ) from his master. Then Imamura Zuigaku studied further under Kano Josen Yukinobu 狩野常川幸信 (1717-1770). These Kano painters were the second and third generation heads of the Hamamachi line of the Kano School respectively. In Meiwa 4 (1767), Imamura Zuigaku was appointed an official painter to the Owari Domain, one of the Three Houses of the Tokugawa (The Tokugawa Gosanke 徳川御三家).

Imamura Zuigaku painted an emaki scroll of the Heiji Monogatari (平治物語絵巻 ), copied from an earlier edition. It is known that this Heiji Monogatari scroll was painted in 1781 (Tenmei 1) for Tokugawa Munechika (1733-1800, ruled 1761-1799), the 9th generation Daimyo of the Owari Domain. Therefore, most likely the present set of highly important emaki scroll paintings were commissioned by imperial decree for Tokugawa Munechika.

Additionally, there is a dating on the colophon corresponding to the 10th month of 1701 (Genroku 14). The reason for this is that Lady Ryoshoin (Tokugawa Ieyasu’s daughter,1565-1615) was in possession of a set of Gosannen War Scroll. However over the years the scrolls (Lady Ryoshoin’s scroll treasure) were damaged. In Genroku 14 (1701), her scrolls were restored in Kyoto. The emperor inspected the scrolls and praised them.

The exterior of each scroll applied with an old paper label showing the title (The Chronicle of the Later Three-Year War) and which volume it is.

Literature comparison:

The emaki by Hidanokami Korehisa dated 1347 (the ‘Gen-e version’), the oldest one among existing picture scrolls on the Gosannen Kassen, is an Important Cultural Property in the collection of the Tokyo National Museum, accession number A-11187. Compare three scrolls with a reproduction of the 1347 scrolls dated 1913, reproduced by the Tokyo Archaeological Association, in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, accession numbers 17.235.9-.11. Compare also closely related but later set of three handscrolls by Sumiyoshi Hirotsura (1793-1863), dated 1853, illustrated in Kaikodo Journal (2000) In the Eye of the Beholder, p. 124-125, no. 31.

Auction comparison:

Compare a scroll (42.3 x 1,928.2 cm) of the first volume, dated to the 18th century, at Christie’s, Japanese Works of Art, 1 November 1996, New York, lot 357 (sold for 14,950 USD, for a single scroll).

Compare to a related singular emaki scroll, measuring 32.5 x 1,624.3 cm, from the Illustrated Scrolls of the Chronicle of Great Peace (vol. II from the set of 12 volumes), dated to mid-17th century, sold at Christie’s, 20 March 1996, New York, lot 407 (sold for USD 288,500).

VOLUME 1

SECTION 1

After hearing that Iehira drove away Governor Yoshiie, Takehira arrives to congratulate Iehira and advise him to move to the more secure and defensible Kanazawa stockade. Takehira and Iehira talk together in the garden while to the left Takehira’s troops set out for the stockade.

SECTION 2

Yoshimitsu, the brother of Shogun Yoshiie, resigns his position in office on account that the Retired Emperor did not grant his appeal to join his brother in the life or death battle against Takehira. Now, with Yoshimitsu on the battlefield, the frontal forces of Yoshiie begin their attack on the Fort. Members of the fort fight back with arrows and one of them injures Kagemasa of Sagami, who fought recklessly against the enemy. The arrow has gone through Kagemasa’s helmet and pierces him in his right eye. Kagemasa breaks off a part of that arrow and throws it back at the enemy, then takes off his helmet to announce his injury. Yoshiie’s soldiers are still unable to break through the fort.

SECTION 3

Governor Yoshiie becomes angry after learning that Takehira has joined allegiance with Iehira and sets off for Kanazawa. The ladies of his household sob at the windows of the house as they watch him mount his horse, which is being held by Mitsutada, an eighty-year-old veteran of the Former Nine Years War but now obliged by age to remain at home, regretful of his inability to join his master.

SECTION 4

As Yoshiie advances on Kanazawa he notices that some flying geese have been disturbed by something in the grass and deduces there are enemy soldiers lying in ambush. Thus, he immediately charges in attack.

SECTION 5

Having begun his attack on the Kanazawa stronghold, Yoshiie initially meets with little success. He therefore begins to seat his warriors according to their bravery in battle that day, the heroes on one side and the cowards on the other, to encourage them all to give their best.

VOLUME 2

SECTION 1

Yoshihiko Hidetake has suggested that the stronghold be surrounded with a blockade to prevent any supplies from being brought into the keep. To pass the time, Takehira proposed that each side choose a champion and have them fight together. In the center of this scene, Onitake on the right and Kametsugu on the left prepare to do battle with naginata (long-handled weapons).

SECTION 2

With Onitake on the verge of winning the bout, Yoshiie’s warriors give a great shout of triumph, at which Takehira’s soldiers pour out of the stronghold to rescue their champion Kametsugu from certain death. In the ensuing carnage one of the fatalities is Korehiro, who had been classed earlier as a coward and was determined to win respect on this day.

SECTION 3

Standing at the top of the fortifications, Sentada, adviser to Iehira, shouts loudly down to Yoshiie: “Your father Yoriyoshi was given much trouble by Sadatada and Munetada during the previous war but he destroyed them with the assistance of our master, who served him loyally. Now you attack his descendants. May you be punished by Heaven for your disloyalty and unfaithfulness.”

SECTION 4

As the stronghold runs short of food, Takehira proposed to Yoshimitsu that they surrender but this offer is refused by Yoshiie. Takehira then invites Yoshimitsu into the castle but Yoshimitsu refused and a warrior named Suekata goes in his place. Takehira asks him to intercede with Yoshiie, and shows him an exceptionally large arrow and asks whose it is. Suekata replies that it is his and returns to his own camp.

SECTION 5

As autumn turns to winter, Yoshiie’s warriors begin to worry that they will freeze to death and write letters to send together with their extra clothes and horses to their families with instructions to sell these belongings and return to Kyoto if they should die. As food becomes scarce, women and children gradually come out but are killed on Hidetake’s advice to keep the remainder within and use up the food remains even faster.

VOLUME 3

SECTION 1

At midnight, Yoshiie wakes up Tomomichi, a thirteen-year old boy sleeping in front of his headquarters, and orders him to tell the men to warm themselves by burning their temporary huts in preparation for the final battle, predicting that the enemy’s castle will fall the next day.

SECTION 2

The scene at Kanazawa on 14 November 1087 is a chaotic hell as Yoshiie’s soldiers chase the enemy as they attempt to escape the burning palace. Takehira hides in a pond but is discovered and taken captive. The women are given over to the soldiers and the surviving men are all killed. Only Iehira escapes, by killing his beloved horse and disguising himself as a commoner.

SECTION 3

With Takehira kneeling before him, Yoshiie recounts the crimes he has committed and orders Oya Mitsufusa to chop off his head. Takehira asks Yoshimitsu for mercy but to no avail. Next, in the scene to the far left, Sentada is brought before Yoshiie, who hates him bitterly for what he shouted from the safety of the fortress. Yoshiie thus orders his tongue to be pulled out and that he be tied to a tree with the head of Takehira beneath him, so that he stands on his dead master’s face. The fortress meanwhile burns to the ground.

SECTION 4

A warrior named Tsugitada has seen the refugees run from the castle and discovers Iehira dressed as a laborer. Tsugitada kills him and presents his head to Yoshiie, who is so delighted that Tsugitada is granted a red robe and horse with saddle.

SECTION 5

Yoshiie makes his report on the war to the court in Kyoto, trying to convince them that he fought on behalf of imperial interests. However, the court disallows the claim, judging that the war had been fought for private purposes. Yoshiie thus understands that he will not receive any reward or even expenses from the court.

Zacke Live Online Bidding

Our online bidding platform makes it easier than ever to bid in our auctions! When you bid through our website, you can take advantage of our premium buyer's terms without incurring any additional online bidding surcharges.

To bid live online, you'll need to create an online account. Once your account is created and your identity is verified, you can register to bid in an auction up to 12 hours before the auction begins.

Intended Spend and Bid Limits

When you register to bid in an online auction, you will need to share your intended maximum spending budget for the auction. We will then review your intended spend and set a bid limit for you. Once you have pre-registered for a live online auction, you can see your intended spend and bid limit by going to 'Account Settings' and clicking on 'Live Bidding Registrations'.

Your bid limit will be the maximum amount you can bid during the auction. Your bid limit is for the hammer price and is not affected by the buyer’s premium and VAT. For example, if you have a bid limit of €1,000 and place two winning bids for €300 and €200, then you will only be able to bid €500 for the rest of the auction. If you try to place a bid that is higher than €500, you will not be able to do so.

Online Absentee and Telephone Bids

You can now leave absentee and telephone bids on our website!

Absentee Bidding

Once you've created an account and your identity is verified, you can leave your absentee bid directly on the lot page. We will contact you when your bids have been confirmed.

Telephone Bidding

Once you've created an account and your identity is verified, you can leave telephone bids online. We will contact you when your bids have been confirmed.

Classic Absentee and Telephone Bidding Form

You can still submit absentee and telephone bids by email or fax if you prefer. Simply fill out the Absentee Bidding/Telephone bidding form and return it to us by email at office@zacke.at or by fax at +43 (1) 532 04 52 20. You can download the PDF from our Upcoming Auctions page.

How-To Guides

How to Create Your Personal Zacke Account

How to Register to Bid on Zacke Live

How to Leave Absentee Bids Online

How to Leave Telephone Bids Online

中文版本的操作指南

创建新账号

注册Zacke Live在线直播竞拍(免平台费)

缺席投标和电话投标

Third-Party Bidding

We partner with best-in-class third-party partners to make it easy for you to bid online in the channel of your choice. Please note that if you bid with one of our third-party online partners, then there will be a live bidding surcharge on top of your final purchase price. You can find all of our fees here. Here's a full list of our third-party partners:

- 51 Bid Live

- EpaiLive

- ArtFoxLive

- Invaluable

- LiveAuctioneers

- the-saleroom

- lot-tissimo

- Drouot

Please note that we place different auctions on different platforms. For example, in general, we only place Chinese art auctions on 51 Bid Live.

Bidding in Person

You must register to bid in person and will be assigned a paddle at the auction. Please contact us at office@zacke.at or +43 (1) 532 04 52 for the latest local health and safety guidelines.