1st Jan, 2020 10:00

Auction Highlights Pre 2020

48

AN EXTREMELY RARE GILT-BRONZE FIGURE OF MANJUSRI, TIBET 14TH CENTURY

Sold for €416,000

including Buyer's Premium

This lot is sold in auction "Fine Chinese Art, Buddhism And Hinduism" on 27.09.2019.

The bodhisattva is finely cast seated in vajraparyankasana on a double lotus base. His hands in gesture of dharmachakra mudra holding the tips of lotus stems bearing his attributes, the sword, khadga, on his right shoulder, and the book, pustaka, on his left shoulder (the book lost).

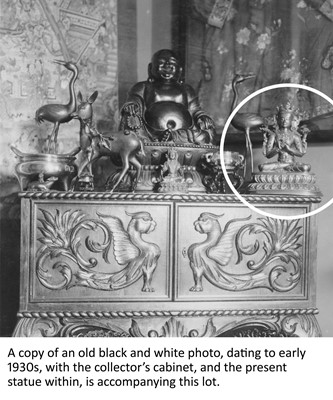

Provenance: From the collection of Alexander Popov in Novi Sad, Kingdom of Serbia, acquired between 1900-1920. A copy of an old black and white photo, dating to early 1930s, with the collector’s cabinet, and the present statue within, is accompanying this lot.

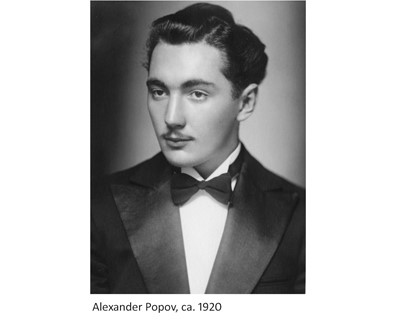

Condition: Magnificent condition with wear and a few casting imperfections and nicks. The book lost. A copper plate marked with a double vajra is evidence of this sculpture’s formal consecration and appears Alexander Popov, ca. 1920 to be the original seal, although it shows an old repair. Some of the many inlaid gemstones and glass beads are lost, most of the remaining ones are original, a few may be later replacements.

Weight: 6.8 kilograms

Dimensions: Height 37.1 cm

This accomplished and substantial sculpture is cast in the graceful manner of the Nepalese artistic tradition, probably at the Newar ateliers of the Kathmandu valley. Limbs are muscular and rounded, the shoulders broad, fingers are long and elegant, and the bodhisattva is imbued with spiritual calm and poise. The fire gilding, the Newar craftsman’s forte, is lustrous and of subtle hue. Moreover, a few of the inlays are made of glass with a garnet tone, a type of inlay typically associated with Nepalese works. The 14th century saw a considerable expansion in the building and extension of Tibetan monastic establishments, and records confirm the employment of Nepalese artists and craftsmen in their construction and decoration. Due to the liberal use of turquoise, as well as the very little remnants of blue pigment in the hair, it is probable that this figure was commissioned for a Tibetan patron.

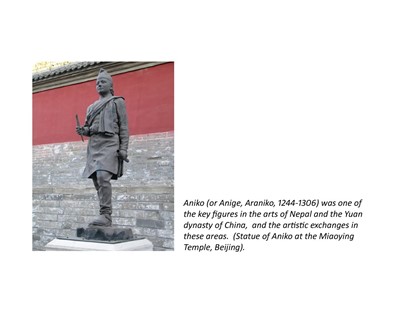

The prowess of the Newar artists was internationally recognized. In 1260 the Mongol emperor Khubilai Khan (1215-1294) commissioned a memorial stupa to Sakya Pandita (1182-1251) to be erected at Sakya monastery in Tibet. Phagspa (1235-1280), the Sakya hierarch and Khubilai’s imperial preceptor, summoned a group of some eighty of the best artists in Nepal to fulfil the charge. Aniko (1244-1306), the group’s leader, was a precocious talent as an architect, weaver, painter and sculptor, and so impressed his sponsor that Phagspa recommended his talents to Khubilai. Aniko was embraced by the emperor and rapidly elevated to prestigious posts. Amongst many honors he was appointed Supervisor-in-chief of All Classes of Artisans, and later Minister of Education in charge of the Imperial Manufactories Commission, responsible for the court’s supply of precious materials such as gold, pearls and rhinoceros horn. Official documents of the Mongol dynasty record Aniko’s biography, and describe monuments, Buddhist sculpture, painting and textiles made to his design, see Karmay (Stoddard), Early Sino-Tibetan Art, Warminster, 1975, pp. 21-24. He was awarded great wealth and status at court. Aniko’s arrival at the Mongol court with twenty-four fellow Newars established a Nepalese presence in the Chinese Imperial workshops that would last for centuries. They brought an invaluable familiarity with Himalayan Buddhist iconography when Tibetan Vajrayana Buddhism became the state religion of the Yuan dynasty, and a renowned ability to adapt to the artistic traditions of a sponsor. Yuan period Chinese works of art that reveal Nepalese influence include a statue of a bodhisattva in the Freer Gallery that is a done in the uniquely Chinese medium of dry lacquer, but with pronounced Newar style in the sculptural detail, ibid., p. 22, pl. 11. An imperial Vajrabhairava mandala in kesi, a favored medium of the Mongol court, is drawn in the Newar style seen in Tibetan paintings associated with Sakya monastery, see James Watt and Ann E. Wardwell, When Silk was Gold, New York, 1997, cat. no. 25. And another Yuan period kesi mandala integrates pure Nepalese scrolling vine motifs with landscape done in the classical Chinese blue-green style; ibid., cat. no. 26. All three works of art are unmistakably Chinese while subtly incorporating Nepalese characteristics.

The present Manjusri meanwhile exemplifies the indigenous Newar sculptural aesthetic of the 14th century: A sculpture made for Tibetan patrons in the prevailing Nepalese style of elegantly modelled, richly gilded and bejeweled statues imbued with spirituality. Indeed, the type of sculpture with which Aniko would have been familiar in his homeland, and with which Phagspa would have sought to fulfil Khubilai’s commission at Sakya monastery. It is one of the finer examples of 14th century sculpture, and a witness to the artistic genius that brought fame to Newar artists throughout the Himalayas, and at the imperial courts of the Yuan, Ming and Qing dynasties.

In the present portrayal, Manjusri wears elaborate bejeweled yajnopavita necklaces, armlets and rosette earrings inlaid with semi-precious stones such as coral, turquoise and lapis lazuli and glass, sometimes with a garnet hue. His dhoti is gathered in beaded folds around his knees, the diaphanous shawl around the shoulders bears finely chased floral motifs, his torso left bare. The face has a serene expression with downcast eyes and an inlaid urna (the inlay lost), the head wearing a high crown secured with a five-leaf diadem, again inlaid, the hair is piled in a chignon with a glass-inlaid vajra helmet on top, his locks falling over his shoulders.

Manjusri, otherwise known as Wenshushili Pusa, is the Bodhisattva of Wisdom. He is often seen in a group of three comprising Shakyamuni and Samantabhadra. Like the present figure, Manjusri is often depicted holding lotus stems supporting the book of wisdom and the sword of knowledge.

Literature comparison: A gilt-bronze figure of Manjusri of similar posture and smaller size (28 cm.), attributing to Tibet, 14th century, is illustrated in On the Path to Enlightenment: The Berti Aschmann Foundation of Tibetan Art at the Museum Rietberg Zurich, Zurich, 1995, no. 64. Compare also to a Nepalese gilt-bronze figure of Manjusri dating to 15th century, in a seated position similarly clad in bejeweled ornaments, but with both hands in the dharmacakra mudra, illustrated in Meinrad Maria Grewenig and Eberhard Rist, Buddha: 2000 Years of Buddhist Art, 232 Masterpieces, Völklingen, 2016, no. 140. Also compare with a Tibetan 14th century gilt copper Manjughosha in Nepalese style housed in the small monastery of Shalu, famous for its important Newar style wall paintings, see von Schroeder, 2001, pl. 229C, p. 959.

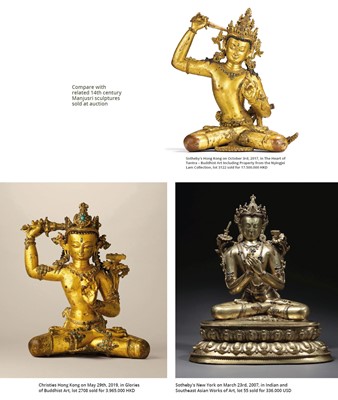

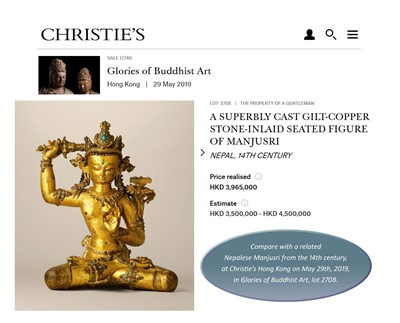

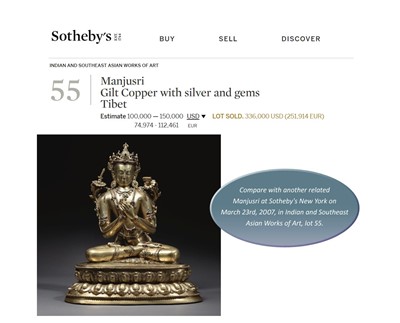

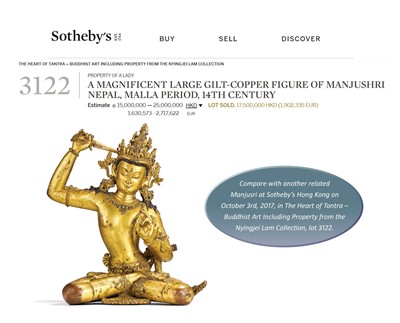

Auction result comparison: Compare with a related Nepalese Manjusri from the 14th century, at Christies Hong Kong on May 29th, 2019, in Glories of Buddhist Art, lot 2708, and another at Sotheby’s New York on March 23rd, 2007, in Indian and Southeast Asian Works of Art, lot 55, and another at Sotheby’s Hong Kong on October 3rd, 2017, in The Heart of Tantra – Buddhist Art Including Property from the Nyingjei Lam Collection, lot 3122.

西藏十四世紀極其罕見的銅鎏金文殊菩薩坐蓮像

菩薩結跏趺坐於雙層蓮臺上,雙手施轉發輪印,並各執蓮枝,蓮花于兩肩処盛開,右側蓮花上置智慧劍,左側蓮花托承般若經(經書遺失) 。

來源: 塞爾維亞 諾維薩Alexander Popov收藏,購於1900-1920年間。隨附一張1930年代黑白照片,上面顯示了這件造像在藏家櫃中的情況。

品相: 品相極好,一些磨損、鑄造缺陷和刻痕。經書遺失。刻有雙金剛的銅板似乎是原始密封銅板,是確認這個雕塑的真實性,雖然它看上去曾經經過修復。 一些鑲嵌寶石和玻璃珠丟失,其餘大部分是原始的,一些也可能是後來的替代品。

重量: 6.8 公斤

尺寸: 高 37.1 厘米

This statue has been X-Rayed. The X-Ray images have been saved on a CD, which will be given to the winning bidder after full payment has been received.

這尊佛像經X光檢驗,檢驗結果保存於光碟中,得標者於付款後會得到此光碟。

This lot is sold in auction "Fine Chinese Art, Buddhism And Hinduism" on 27.09.2019.

The bodhisattva is finely cast seated in vajraparyankasana on a double lotus base. His hands in gesture of dharmachakra mudra holding the tips of lotus stems bearing his attributes, the sword, khadga, on his right shoulder, and the book, pustaka, on his left shoulder (the book lost).

Provenance: From the collection of Alexander Popov in Novi Sad, Kingdom of Serbia, acquired between 1900-1920. A copy of an old black and white photo, dating to early 1930s, with the collector’s cabinet, and the present statue within, is accompanying this lot.

Condition: Magnificent condition with wear and a few casting imperfections and nicks. The book lost. A copper plate marked with a double vajra is evidence of this sculpture’s formal consecration and appears Alexander Popov, ca. 1920 to be the original seal, although it shows an old repair. Some of the many inlaid gemstones and glass beads are lost, most of the remaining ones are original, a few may be later replacements.

Weight: 6.8 kilograms

Dimensions: Height 37.1 cm

This accomplished and substantial sculpture is cast in the graceful manner of the Nepalese artistic tradition, probably at the Newar ateliers of the Kathmandu valley. Limbs are muscular and rounded, the shoulders broad, fingers are long and elegant, and the bodhisattva is imbued with spiritual calm and poise. The fire gilding, the Newar craftsman’s forte, is lustrous and of subtle hue. Moreover, a few of the inlays are made of glass with a garnet tone, a type of inlay typically associated with Nepalese works. The 14th century saw a considerable expansion in the building and extension of Tibetan monastic establishments, and records confirm the employment of Nepalese artists and craftsmen in their construction and decoration. Due to the liberal use of turquoise, as well as the very little remnants of blue pigment in the hair, it is probable that this figure was commissioned for a Tibetan patron.

The prowess of the Newar artists was internationally recognized. In 1260 the Mongol emperor Khubilai Khan (1215-1294) commissioned a memorial stupa to Sakya Pandita (1182-1251) to be erected at Sakya monastery in Tibet. Phagspa (1235-1280), the Sakya hierarch and Khubilai’s imperial preceptor, summoned a group of some eighty of the best artists in Nepal to fulfil the charge. Aniko (1244-1306), the group’s leader, was a precocious talent as an architect, weaver, painter and sculptor, and so impressed his sponsor that Phagspa recommended his talents to Khubilai. Aniko was embraced by the emperor and rapidly elevated to prestigious posts. Amongst many honors he was appointed Supervisor-in-chief of All Classes of Artisans, and later Minister of Education in charge of the Imperial Manufactories Commission, responsible for the court’s supply of precious materials such as gold, pearls and rhinoceros horn. Official documents of the Mongol dynasty record Aniko’s biography, and describe monuments, Buddhist sculpture, painting and textiles made to his design, see Karmay (Stoddard), Early Sino-Tibetan Art, Warminster, 1975, pp. 21-24. He was awarded great wealth and status at court. Aniko’s arrival at the Mongol court with twenty-four fellow Newars established a Nepalese presence in the Chinese Imperial workshops that would last for centuries. They brought an invaluable familiarity with Himalayan Buddhist iconography when Tibetan Vajrayana Buddhism became the state religion of the Yuan dynasty, and a renowned ability to adapt to the artistic traditions of a sponsor. Yuan period Chinese works of art that reveal Nepalese influence include a statue of a bodhisattva in the Freer Gallery that is a done in the uniquely Chinese medium of dry lacquer, but with pronounced Newar style in the sculptural detail, ibid., p. 22, pl. 11. An imperial Vajrabhairava mandala in kesi, a favored medium of the Mongol court, is drawn in the Newar style seen in Tibetan paintings associated with Sakya monastery, see James Watt and Ann E. Wardwell, When Silk was Gold, New York, 1997, cat. no. 25. And another Yuan period kesi mandala integrates pure Nepalese scrolling vine motifs with landscape done in the classical Chinese blue-green style; ibid., cat. no. 26. All three works of art are unmistakably Chinese while subtly incorporating Nepalese characteristics.

The present Manjusri meanwhile exemplifies the indigenous Newar sculptural aesthetic of the 14th century: A sculpture made for Tibetan patrons in the prevailing Nepalese style of elegantly modelled, richly gilded and bejeweled statues imbued with spirituality. Indeed, the type of sculpture with which Aniko would have been familiar in his homeland, and with which Phagspa would have sought to fulfil Khubilai’s commission at Sakya monastery. It is one of the finer examples of 14th century sculpture, and a witness to the artistic genius that brought fame to Newar artists throughout the Himalayas, and at the imperial courts of the Yuan, Ming and Qing dynasties.

In the present portrayal, Manjusri wears elaborate bejeweled yajnopavita necklaces, armlets and rosette earrings inlaid with semi-precious stones such as coral, turquoise and lapis lazuli and glass, sometimes with a garnet hue. His dhoti is gathered in beaded folds around his knees, the diaphanous shawl around the shoulders bears finely chased floral motifs, his torso left bare. The face has a serene expression with downcast eyes and an inlaid urna (the inlay lost), the head wearing a high crown secured with a five-leaf diadem, again inlaid, the hair is piled in a chignon with a glass-inlaid vajra helmet on top, his locks falling over his shoulders.

Manjusri, otherwise known as Wenshushili Pusa, is the Bodhisattva of Wisdom. He is often seen in a group of three comprising Shakyamuni and Samantabhadra. Like the present figure, Manjusri is often depicted holding lotus stems supporting the book of wisdom and the sword of knowledge.

Literature comparison: A gilt-bronze figure of Manjusri of similar posture and smaller size (28 cm.), attributing to Tibet, 14th century, is illustrated in On the Path to Enlightenment: The Berti Aschmann Foundation of Tibetan Art at the Museum Rietberg Zurich, Zurich, 1995, no. 64. Compare also to a Nepalese gilt-bronze figure of Manjusri dating to 15th century, in a seated position similarly clad in bejeweled ornaments, but with both hands in the dharmacakra mudra, illustrated in Meinrad Maria Grewenig and Eberhard Rist, Buddha: 2000 Years of Buddhist Art, 232 Masterpieces, Völklingen, 2016, no. 140. Also compare with a Tibetan 14th century gilt copper Manjughosha in Nepalese style housed in the small monastery of Shalu, famous for its important Newar style wall paintings, see von Schroeder, 2001, pl. 229C, p. 959.

Auction result comparison: Compare with a related Nepalese Manjusri from the 14th century, at Christies Hong Kong on May 29th, 2019, in Glories of Buddhist Art, lot 2708, and another at Sotheby’s New York on March 23rd, 2007, in Indian and Southeast Asian Works of Art, lot 55, and another at Sotheby’s Hong Kong on October 3rd, 2017, in The Heart of Tantra – Buddhist Art Including Property from the Nyingjei Lam Collection, lot 3122.

西藏十四世紀極其罕見的銅鎏金文殊菩薩坐蓮像

菩薩結跏趺坐於雙層蓮臺上,雙手施轉發輪印,並各執蓮枝,蓮花于兩肩処盛開,右側蓮花上置智慧劍,左側蓮花托承般若經(經書遺失) 。

來源: 塞爾維亞 諾維薩Alexander Popov收藏,購於1900-1920年間。隨附一張1930年代黑白照片,上面顯示了這件造像在藏家櫃中的情況。

品相: 品相極好,一些磨損、鑄造缺陷和刻痕。經書遺失。刻有雙金剛的銅板似乎是原始密封銅板,是確認這個雕塑的真實性,雖然它看上去曾經經過修復。 一些鑲嵌寶石和玻璃珠丟失,其餘大部分是原始的,一些也可能是後來的替代品。

重量: 6.8 公斤

尺寸: 高 37.1 厘米

This statue has been X-Rayed. The X-Ray images have been saved on a CD, which will be given to the winning bidder after full payment has been received.

這尊佛像經X光檢驗,檢驗結果保存於光碟中,得標者於付款後會得到此光碟。

Interested in buying one of these pieces?

Please contact us at office@zacke.at or +43 (1) 532 04 52. Prices already include Buyer's Premium. The price you see here is the final price you will end up paying.