29th Sep, 2022 13:00

DAY 1 - TWO-DAY AUCTION - Fine Chinese Art / 中國藝術集珍 / Buddhism & Hinduism

220

† A MONUMENTAL AND HIGHLY IMPORTANT SANDSTONE FIGURE OF BUDDHA, PRE-ANGKOR PERIOD

Sold for €64,000

including Buyer's Premium

Mekong Delta, present-day Cambodia and Vietnam, 6th-7th century. Superbly carved standing with each foot on a separate lotus dais, wearing a diaphanous sanghati, the folds elegantly draped over his left shoulder and elbow, gathered at the ankles. The serene face sensitively drawn with heavy-lidded eyes, the sinuous lids and round pupils neatly incised, gently arched brows, and full lips, flanked by long pendulous earlobes, the hair arranged in snail-shell curls surmounted by a tall ushnisha.

Provenance: From a notable collector in London, United Kingdom.

Condition: Magnificent condition, commensurate with age. Extensive wear, encrustations, losses, signs of weathering and erosion, minor nicks, cracks and scratches. Fine, naturally grown patina overall.

Dimensions: Height of figure excluding base and tang: 146.5 cm. Height of figure including tang, but excluding base: 190 cm. Height including base: 196 cm.

The youthful-looking Buddha presents an elegant image that acts as a metaphor for his spiritual perfection. He stands on two lotus flowers, which probably identifies him as one of the esoteric Buddhas, depicted in Nirvana or another of the heavenly realms. This is the serene eternal state of one who is removed from the passage of time and the emotional issues of the human sphere. He has caused the lotuses to bloom and as they support his weightless form, they symbolize his purity of thought.

The earliest stone sculptures of the region were created in the Mekong Delta, now shared by Cambodia and Vietnam, where Indian trading communities introduced their own Buddhist and Hindu beliefs. Contacts with regions to the north and China were also strengthened by trade. This Buddha retains elements of form that are associated with India while the two lotuses, rather than one, on which he stands indicate a Chinese influence. His appearance has been transformed by the introduction of a purely regional aesthetic, however. Separated from the South Asian sangha (religious establishment), local devotees came to see the Buddhist faith as their own and consequently endorsed their beliefs with images resembling themselves.

Buddhism had reached Southeast Asia by the 1st century AD, largely thanks to its popularity amongst Indian merchants who established trading communities around the Mekong Delta. They initially sourced gold in the region but found other rare commodities such as ivory, gemstones, minerals and fine woods for markets both at home and further west. As a result, the Mekong Delta became part of a wider trading network linking the China Seas with the Roman Empire. There are epigraphical accounts describing the journeys on merchant ships of Buddhist missionaries from southern India and Sri Lanka, but the earliest visual record of stone sculptures indicates that evangelists from northern India and possibly Gandhara and China were also active in the region.

International trading predated the establishment of diplomatic links between the rulers of the Mekong Delta with China in the 3rd century and various Indian kings in the 4th century. Indian and to a lesser extent Chinese culture gradually infiltrated the region’s hierarchy and while the higher echelons were attracted to the Buddhist and Hindu faiths, the vast majority of the people maintained their traditional beliefs.

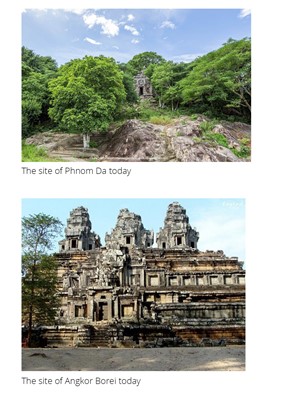

A number of cities linked by canals existed in the Delta region, including the extensive sites of Oc Eo, Phnom Da, and Angkor Borei, which may have been autonomous principalities or part of a confederation. Along with the adjacent Phnom Da, Angkor Borei was a notable ritual center; its influence outlived the eclipse of Funan, perhaps through association with an ancestral cult. Buddhism and Hinduism had a unifying effect to some extent but within the region, devotees only adopted those aspects of the Indian faiths that were relevant to their needs; these probably varied from place to place. It is possible that the Buddha and Hindu gods were honored with temples and statues, emulating those of India, in order to bolster the political or social status of their Southeast Asian adherents.

Chinese writers left a number of accounts describing the kingdom of Funan in the Mekong Delta, that led French scholars of the 19th and early 20th centuries to conclude that it was a great power whose influence stretched across much of Southeast Asia. During the last thirty years, however, an intensive amount of archaeological investigation in Southeast Asia has led to a reappraisal of the work carried out by the Ecole Française d’Extrème Orient during the French colonial period. This in no way diminishes the achievement of archaeologists such as Louis Mallaret, historians, for example Paul Pelliot and art historians including Pierre Dupont; rather, it places their work in a different context. The French believed that Funan was politically dominant until the 7th century but scholars now suggest that a number of small rival principalities existed, possibly city states whose strength and influence depended on changing political and economic circumstances. We do not know the names the inhabitants gave their homelands; Funan was a Chinese attempt at recording a local name, possibly ‘Phnom’ (meaning ‘mountain’). Funan may have spread its influence along the coast as far as the Malay Peninsula, but it is more likely that this was through the establishment of trading posts rather than political control. The French believed that a single culture spread through much of mainland Southeast Asia, but this is not strictly accurate. Away from the coast, communities were scattered and remote from one another, although ethnic groups shared certain spiritual ideas concerning village and nature deities.

Expert’s note: A detailed academic commentary on the present lot, elaborating on the history and art of Funan as well as the evolution of Buddhist images in the Mekong Delta, and showing many further comparisons to examples in private and public collections, is available upon request..To receive a PDF copy of this academic dossier, please refer to the department.

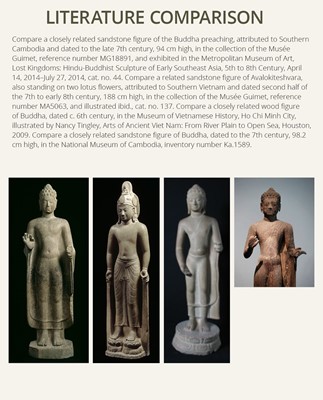

Literature comparison:

Compare a closely related sandstone figure of the Buddha preaching, attributed to Southern Cambodia and dated to the late 7th century, 94 cm high, in the collection of the Musée Guimet, reference number MG18891, and exhibited in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Lost Kingdoms: Hindu-Buddhist Sculpture of Early Southeast Asia, 5th to 8th Century, April 14, 2014–July 27, 2014, cat. no. 44. Compare a related sandstone figure of Avalokiteshvara, also standing on two lotus flowers, attributed to Southern Vietnam and dated second half of the 7th to early 8th century, 188 cm high, in the collection of the Musée Guimet, reference number MA5063, and illustrated ibid., cat. no. 137. Compare a closely related wood figure of Buddha, dated c. 6th century, in the Museum of Vietnamese History, Ho Chi Minh City, illustrated by Nancy Tingley, Arts of Ancient Viet Nam: From River Plain to Open Sea, Houston, 2009. Compare a closely related sandstone figure of Buddha, dated to the 7th century, 98.2 cm high, in the National Museum of Cambodia, inventory number Ka.1589.

Auction result comparison:

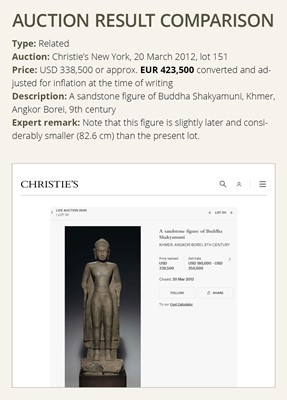

Type: Related

Auction: Christie’s New York, 20 March 2012, lot 151

Price: USD 338,500 or approx. EUR 423,500 converted and adjusted for inflation at the time of writing

Description: A sandstone figure of Buddha Shakyamuni, Khmer, Angkor Borei, 9th century

Expert remark: Note that this figure is slightly later and considerably smaller (82.6 cm) than the present lot.

Auction result comparison:

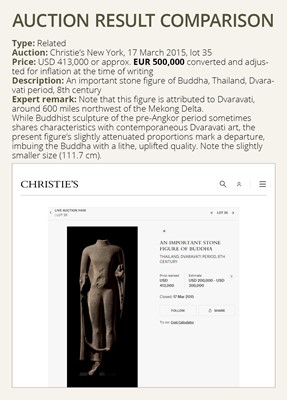

Type: Related

Auction: Christie’s New York, 17 March 2015, lot 35

Price: USD 413,000 or approx. EUR 500,000 converted and adjusted for inflation at the time of writing

Description: An important stone figure of Buddha, Thailand, Dvaravati period, 8th century

Expert remark: Note that this figure is attributed to Dvaravati, around 600 miles northwest of the Mekong Delta. While Buddhist sculpture of the pre-Angkor period sometimes shares characteristics with contemporaneous Dvaravati art, the present figure's slightly attenuated proportions mark a departure, imbuing the Buddha with a lithe, uplifted quality. Note the slightly smaller size (111.7 cm).

Mekong Delta, present-day Cambodia and Vietnam, 6th-7th century. Superbly carved standing with each foot on a separate lotus dais, wearing a diaphanous sanghati, the folds elegantly draped over his left shoulder and elbow, gathered at the ankles. The serene face sensitively drawn with heavy-lidded eyes, the sinuous lids and round pupils neatly incised, gently arched brows, and full lips, flanked by long pendulous earlobes, the hair arranged in snail-shell curls surmounted by a tall ushnisha.

Provenance: From a notable collector in London, United Kingdom.

Condition: Magnificent condition, commensurate with age. Extensive wear, encrustations, losses, signs of weathering and erosion, minor nicks, cracks and scratches. Fine, naturally grown patina overall.

Dimensions: Height of figure excluding base and tang: 146.5 cm. Height of figure including tang, but excluding base: 190 cm. Height including base: 196 cm.

The youthful-looking Buddha presents an elegant image that acts as a metaphor for his spiritual perfection. He stands on two lotus flowers, which probably identifies him as one of the esoteric Buddhas, depicted in Nirvana or another of the heavenly realms. This is the serene eternal state of one who is removed from the passage of time and the emotional issues of the human sphere. He has caused the lotuses to bloom and as they support his weightless form, they symbolize his purity of thought.

The earliest stone sculptures of the region were created in the Mekong Delta, now shared by Cambodia and Vietnam, where Indian trading communities introduced their own Buddhist and Hindu beliefs. Contacts with regions to the north and China were also strengthened by trade. This Buddha retains elements of form that are associated with India while the two lotuses, rather than one, on which he stands indicate a Chinese influence. His appearance has been transformed by the introduction of a purely regional aesthetic, however. Separated from the South Asian sangha (religious establishment), local devotees came to see the Buddhist faith as their own and consequently endorsed their beliefs with images resembling themselves.

Buddhism had reached Southeast Asia by the 1st century AD, largely thanks to its popularity amongst Indian merchants who established trading communities around the Mekong Delta. They initially sourced gold in the region but found other rare commodities such as ivory, gemstones, minerals and fine woods for markets both at home and further west. As a result, the Mekong Delta became part of a wider trading network linking the China Seas with the Roman Empire. There are epigraphical accounts describing the journeys on merchant ships of Buddhist missionaries from southern India and Sri Lanka, but the earliest visual record of stone sculptures indicates that evangelists from northern India and possibly Gandhara and China were also active in the region.

International trading predated the establishment of diplomatic links between the rulers of the Mekong Delta with China in the 3rd century and various Indian kings in the 4th century. Indian and to a lesser extent Chinese culture gradually infiltrated the region’s hierarchy and while the higher echelons were attracted to the Buddhist and Hindu faiths, the vast majority of the people maintained their traditional beliefs.

A number of cities linked by canals existed in the Delta region, including the extensive sites of Oc Eo, Phnom Da, and Angkor Borei, which may have been autonomous principalities or part of a confederation. Along with the adjacent Phnom Da, Angkor Borei was a notable ritual center; its influence outlived the eclipse of Funan, perhaps through association with an ancestral cult. Buddhism and Hinduism had a unifying effect to some extent but within the region, devotees only adopted those aspects of the Indian faiths that were relevant to their needs; these probably varied from place to place. It is possible that the Buddha and Hindu gods were honored with temples and statues, emulating those of India, in order to bolster the political or social status of their Southeast Asian adherents.

Chinese writers left a number of accounts describing the kingdom of Funan in the Mekong Delta, that led French scholars of the 19th and early 20th centuries to conclude that it was a great power whose influence stretched across much of Southeast Asia. During the last thirty years, however, an intensive amount of archaeological investigation in Southeast Asia has led to a reappraisal of the work carried out by the Ecole Française d’Extrème Orient during the French colonial period. This in no way diminishes the achievement of archaeologists such as Louis Mallaret, historians, for example Paul Pelliot and art historians including Pierre Dupont; rather, it places their work in a different context. The French believed that Funan was politically dominant until the 7th century but scholars now suggest that a number of small rival principalities existed, possibly city states whose strength and influence depended on changing political and economic circumstances. We do not know the names the inhabitants gave their homelands; Funan was a Chinese attempt at recording a local name, possibly ‘Phnom’ (meaning ‘mountain’). Funan may have spread its influence along the coast as far as the Malay Peninsula, but it is more likely that this was through the establishment of trading posts rather than political control. The French believed that a single culture spread through much of mainland Southeast Asia, but this is not strictly accurate. Away from the coast, communities were scattered and remote from one another, although ethnic groups shared certain spiritual ideas concerning village and nature deities.

Expert’s note: A detailed academic commentary on the present lot, elaborating on the history and art of Funan as well as the evolution of Buddhist images in the Mekong Delta, and showing many further comparisons to examples in private and public collections, is available upon request..To receive a PDF copy of this academic dossier, please refer to the department.

Literature comparison:

Compare a closely related sandstone figure of the Buddha preaching, attributed to Southern Cambodia and dated to the late 7th century, 94 cm high, in the collection of the Musée Guimet, reference number MG18891, and exhibited in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Lost Kingdoms: Hindu-Buddhist Sculpture of Early Southeast Asia, 5th to 8th Century, April 14, 2014–July 27, 2014, cat. no. 44. Compare a related sandstone figure of Avalokiteshvara, also standing on two lotus flowers, attributed to Southern Vietnam and dated second half of the 7th to early 8th century, 188 cm high, in the collection of the Musée Guimet, reference number MA5063, and illustrated ibid., cat. no. 137. Compare a closely related wood figure of Buddha, dated c. 6th century, in the Museum of Vietnamese History, Ho Chi Minh City, illustrated by Nancy Tingley, Arts of Ancient Viet Nam: From River Plain to Open Sea, Houston, 2009. Compare a closely related sandstone figure of Buddha, dated to the 7th century, 98.2 cm high, in the National Museum of Cambodia, inventory number Ka.1589.

Auction result comparison:

Type: Related

Auction: Christie’s New York, 20 March 2012, lot 151

Price: USD 338,500 or approx. EUR 423,500 converted and adjusted for inflation at the time of writing

Description: A sandstone figure of Buddha Shakyamuni, Khmer, Angkor Borei, 9th century

Expert remark: Note that this figure is slightly later and considerably smaller (82.6 cm) than the present lot.

Auction result comparison:

Type: Related

Auction: Christie’s New York, 17 March 2015, lot 35

Price: USD 413,000 or approx. EUR 500,000 converted and adjusted for inflation at the time of writing

Description: An important stone figure of Buddha, Thailand, Dvaravati period, 8th century

Expert remark: Note that this figure is attributed to Dvaravati, around 600 miles northwest of the Mekong Delta. While Buddhist sculpture of the pre-Angkor period sometimes shares characteristics with contemporaneous Dvaravati art, the present figure's slightly attenuated proportions mark a departure, imbuing the Buddha with a lithe, uplifted quality. Note the slightly smaller size (111.7 cm).

Zacke Live Online Bidding

Our online bidding platform makes it easier than ever to bid in our auctions! When you bid through our website, you can take advantage of our premium buyer's terms without incurring any additional online bidding surcharges.

To bid live online, you'll need to create an online account. Once your account is created and your identity is verified, you can register to bid in an auction up to 12 hours before the auction begins.

Intended Spend and Bid Limits

When you register to bid in an online auction, you will need to share your intended maximum spending budget for the auction. We will then review your intended spend and set a bid limit for you. Once you have pre-registered for a live online auction, you can see your intended spend and bid limit by going to 'Account Settings' and clicking on 'Live Bidding Registrations'.

Your bid limit will be the maximum amount you can bid during the auction. Your bid limit is for the hammer price and is not affected by the buyer’s premium and VAT. For example, if you have a bid limit of €1,000 and place two winning bids for €300 and €200, then you will only be able to bid €500 for the rest of the auction. If you try to place a bid that is higher than €500, you will not be able to do so.

Online Absentee and Telephone Bids

You can now leave absentee and telephone bids on our website!

Absentee Bidding

Once you've created an account and your identity is verified, you can leave your absentee bid directly on the lot page. We will contact you when your bids have been confirmed.

Telephone Bidding

Once you've created an account and your identity is verified, you can leave telephone bids online. We will contact you when your bids have been confirmed.

Classic Absentee and Telephone Bidding Form

You can still submit absentee and telephone bids by email or fax if you prefer. Simply fill out the Absentee Bidding/Telephone bidding form and return it to us by email at office@zacke.at or by fax at +43 (1) 532 04 52 20. You can download the PDF from our Upcoming Auctions page.

How-To Guides

How to Create Your Personal Zacke Account

How to Register to Bid on Zacke Live

How to Leave Absentee Bids Online

How to Leave Telephone Bids Online

中文版本的操作指南

创建新账号

注册Zacke Live在线直播竞拍(免平台费)

缺席投标和电话投标

Third-Party Bidding

We partner with best-in-class third-party partners to make it easy for you to bid online in the channel of your choice. Please note that if you bid with one of our third-party online partners, then there will be a live bidding surcharge on top of your final purchase price. You can find all of our fees here. Here's a full list of our third-party partners:

- 51 Bid Live

- EpaiLive

- ArtFoxLive

- Invaluable

- LiveAuctioneers

- the-saleroom

- lot-tissimo

- Drouot

Please note that we place different auctions on different platforms. For example, in general, we only place Chinese art auctions on 51 Bid Live.

Bidding in Person

You must register to bid in person and will be assigned a paddle at the auction. Please contact us at office@zacke.at or +43 (1) 532 04 52 for the latest local health and safety guidelines.